Porting Stunt Car Racer to the Commodore Plus/4

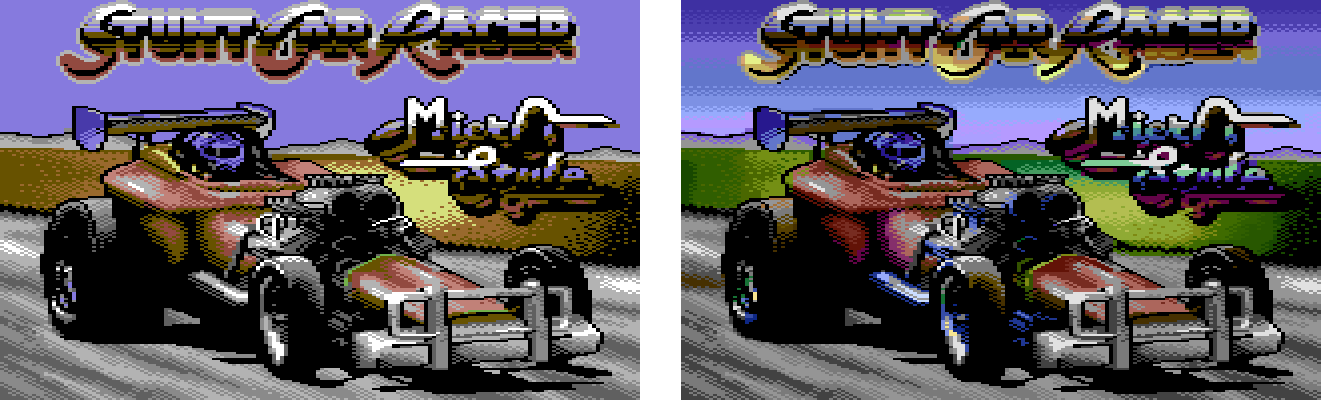

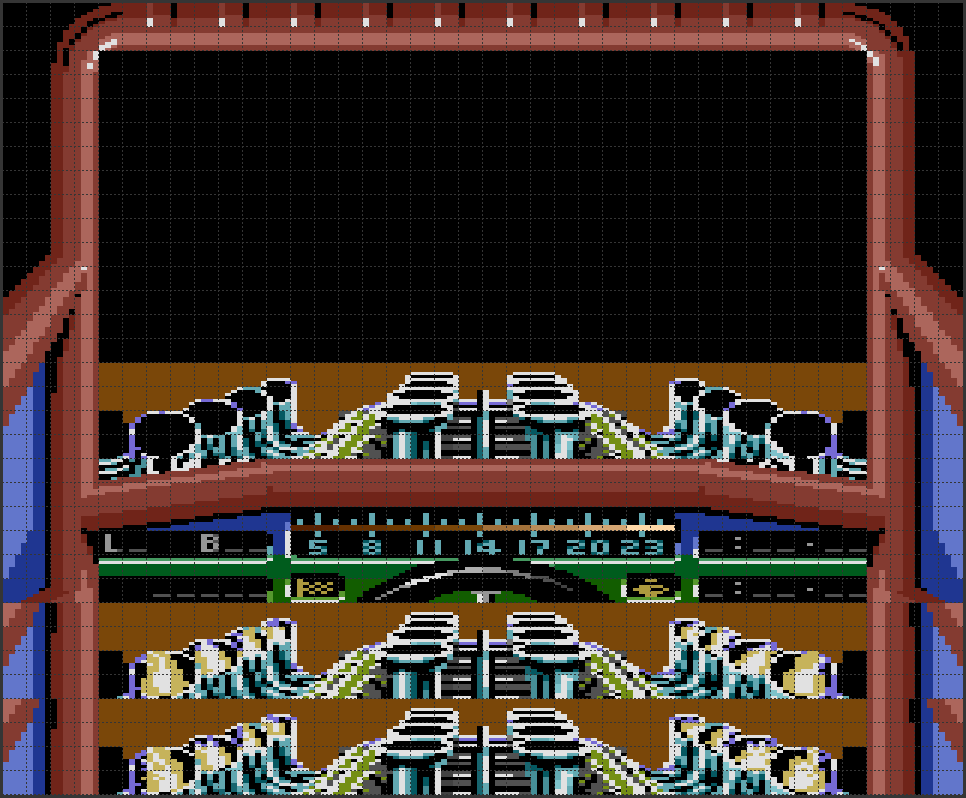

I just recently released the Plus/4 port of Stunt Car Racer. If you don’t have real hardware to play it on, which is probably the case for most readers, I recommend the Yape emulator to try it. In this article I’ll give a high-level overview of how I adapted the C64 version of the game to its not-so-successful little cousin. For context, here’s what the end result looks like:

A Little History

Stunt Car Racer is one of the most sophisticated games from the 8-bit era. You’re not going to find many other examples of filled-vector 3D rendering combined with a physics engine that resolves spring collisions against a 3D mesh while still delivering a decent frame rate running on a 1 MHz CPU and no assistance from the hardware whatsoever. Phew, it’s quite a mouthful to just list those features!

The game was originally developed for the C64, but thanks to the fact that it didn’t lean heavily on the specific features of the platform, it received very competent ports for other popular systems of the time: Amstrad CPC, ZX Spectrum, Amiga, Atari ST and even PCs running MS-DOS. Apparently there was an unreleased version for the NES as well. In the modern era of homebrew conversions, this list got extended even further: first the Atari 8-bit family, then the BBC Master and also the Atari Jaguar. It’s starting to look a bit like Doom with this proliferation of ports, and I think the comparison is apt in many ways. Geoff Crammond was no less of a technological limit-pusher in the sim racing genre than John Carmack in the world of FPSs.

I originally wanted to study Stunt Car Racer because I thought it would be a good example of doing advanced maths on the 6502, something I needed for one of my own projects. After dissecting the game and learning how every single bit of its engine works, I got inspired to try hacking it so the physics simulation would run at 50 FPS instead of the original 7, because there are both vintage and modern hardware accessories that allow running C64 games at higher clock rates, notably 20 MHz. This is the so-called SuperCPU edition you can download here.

At the same time, there has been a resurgence of excellent ports of high-profile games for the Commodore Plus/4 recently, e.g. Impossible Mission or Lemmings. Having noticed this trend, I started digging and found out that nobody had ever given a serious attempt at porting Stunt Car Racer to this platform. Now who could resist the temptation to fulfil a 30-year dream?

Comparing the Commodores

To understand the scope of this venture we need to briefly look at the similarities and differences between the two platforms. The Plus/4 sports a new graphics chip called TED, which is derived from the C64’s VIC-II. It has the same screen modes with the same resolution and memory layout as the C64.

On the plus side, the TED expands the colour palette to 121 entries with a luma-chroma system to catch up with the contemporary Atari systems in this regard. It also gets access to the full 16-bit address range, unlike the VIC that relied on bank switching, plus it removes an annoying C64 feature where the VIC would be hard-wired to see character ROM in certain address ranges, thereby making 2 of the 8 possible bitmap screens unusable.

Unfortunately, hardware support for sprites was left on the cost-cutting board, which made the system a difficult target for action games of any sort. Without hardware sprites, a lot of CPU time needs to be spent on shifting and blitting, plus there’s colour clash reminiscent of the much cheaper ZX Spectrum (although multicolour mode makes it possible to work around it better). The increased bandwidth requirement of the bigger palette also led to another limitation: multicolour bitmaps only get two unique colours per character block as opposed to the C64’s three.

Here’s a summary of the above in table form (bold meaning the better of the two):

| Feature | VIC-II (C64) | TED (C+4) |

|---|---|---|

| Addressable Range | 16K | 64K |

| Hard-Wired Character ROM | Yes | No |

| Character Mode | Yes | Yes |

| Bitmap Mode | Yes | Yes |

| Hi-res | Yes | Yes |

| Multicolour | Yes | Yes |

| Hardware Sprites | Yes | No |

| Palette Size | 16 | 121 |

| Unique MC Colours Per Block | 3 | 2 |

Stunt Car Racer, Finally

Stunt Car Racer doesn’t rely on sprite support very much, which is what allowed its ports to the Z80-based platforms in the first place. Since this gets rid of the biggest disadvantage of the Plus/4, the main concern was to adapt the 3D rendering engine, and that was the first thing I did.

Rendering the Framebuffer

The game uses multicolour bitmap mode and relies on double buffering to be able to work on the upcoming frame in the background. To achieve the filled vector look, Crammond came up with a clever hack: just render everything in wireframe, then make sure to fill the sky and the ground with different colours. His solution takes advantage of colour attributes to speed up this process where a character block is fully covered by either the ground or the sky, and patches up the seam between the two.

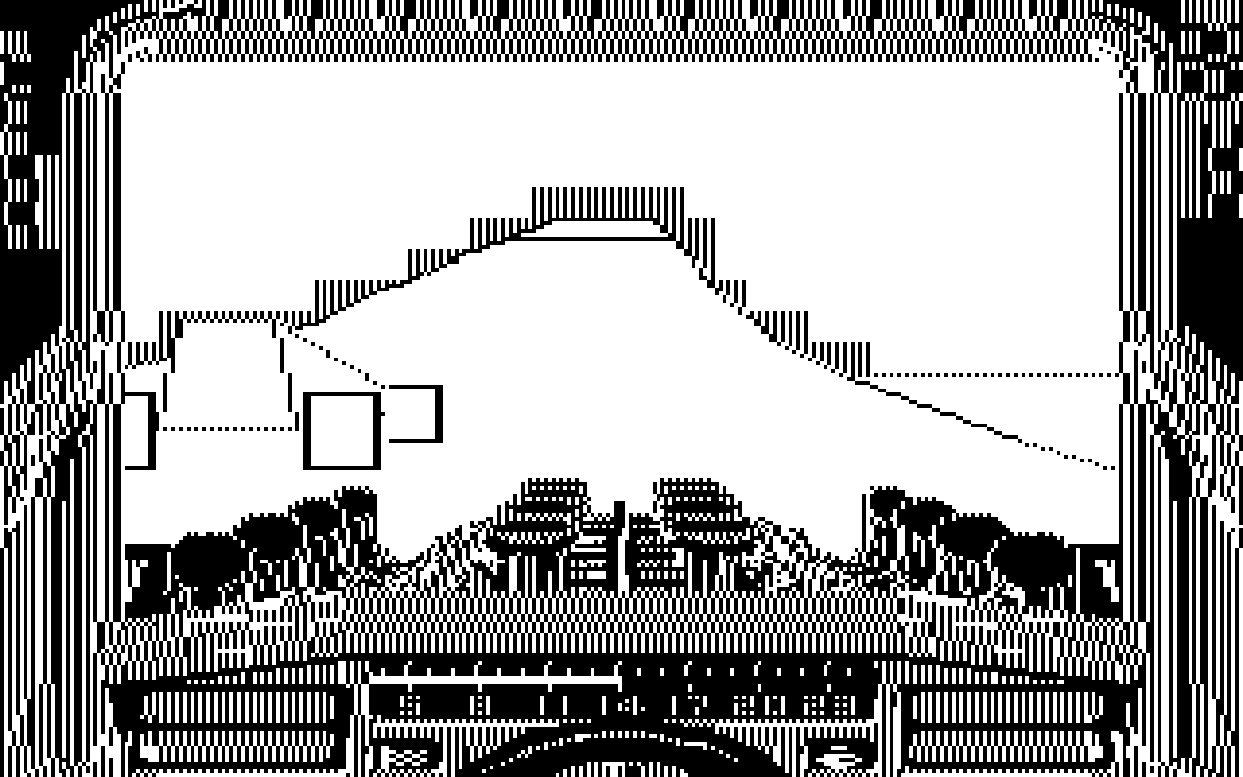

Let’s look at an example. The sprites are marked with red frames, they are not part of the bitmap, hence not relevant to the renderer. We’ll get back to them later!

In order to achieve the above look, the underlying bits are the following (black for zeroes and white for ones):

There are a few things to note here. One amusing bit is that in typical Geoff Crammond fashion the screen contains some data hidden in the black parts around the frame of the cockpit. In this case it’s the checkerboard pattern used in the border for the track preview shown just before starting a race. He already pulled a similar trick in his earlier racing game, Revs.

What’s more important is that a multicolour pixel takes two bits under the hood. Both the ground and the sky are mostly filled with 1s, and the colour of these parts is determined by the contents of the colour RAM. Black pixels are plotted with 00 (since black is the background colour), white pixels are represented by 01, and when a block is shared by both the sky and the ground, sky pixels are plotted with 10 while the block’s individual 11 colour is set to that of the ground.

This is a very smart and convenient solution, because starting with a buffer filled with 1s all colours can be plotted by ANDing various bit masks, which is exactly what the renderer does.

Unfortunately, this system presents us with a problem when trying to adapt it to the Plus/4. To understand why, let’s look at how multicolour bitmap pixels are defined on the two platforms. The bold entries mark the colours that can be defined uniquely per character block, the others are common across the whole screen (we’re ignoring the possiblity of changing them halfway during raster scanning, as it’s irrelevant for Stunt Car Racer, but of course that would be possible otherwise):

| Bit Pattern | VIC-II | TED |

|---|---|---|

| 00 | Background ($d021) | Background ($ff15) |

| 01 | Screen Matrix | Screen Matrix |

| 10 | Screen Matrix | Screen Matrix |

| 11 | Colour RAM | Foreground ($ff16) |

The problem is that the 11 pattern belongs to one of the common colours, which makes it unsuitable for the quick sky tinting logic. Also, we want white to be the other common colour besides black to be able to draw the rest of the screen properly. To make it work with the TED, I had to redefine the underlying representation as follows:

| Colour | VIC-II | TED |

|---|---|---|

| Ground/Sky | 11 | 01 |

| Black | 00 | 00 |

| White | 01 | 11 |

| Sky | 10 | 10 |

This means that the operations required to plot each of those elements change completely:

| Colour | VIC-II | TED |

|---|---|---|

| Ground/Sky | - | - |

| Black | AND 00 | AND 00 |

| White | AND 01 | OR 11 |

| Sky | AND 10 | XOR 11 |

Also, due to the 11 pattern showing as white across the whole screen, we cannot use the trick to hide arbitrary data in the black parts any more, so in the Plus/4 version I decided to stash the checkerboard pattern elsewhere. I only realised after release that this was unnecessary, since there’s not a single 11 pixel in those patterns… Well, that’s only 192 bytes wasted, not the end of the world, since I had more to spare in the end.

Updating the Colour Attributes

The C64 version uses the colour RAM to quickly update the sky-ground separation for whole characters. This is a piece of memory outside the main RAM that cannot be double-buffered (a shortcoming later fixed in the C128), so its update needs to be timed carefully around the position of the raster beam.

When the game is done rendering the next frame and the only thing missing is the colour update, it makes sure to set a flag in a raster interrupt at the bottom of the 3D viewport, in the region covered by the front of the car. While waiting for the raster beam to hit that region, it already starts processing the physics calculations for the subsequent frame. It polls the flag between various phases of the simulation, and if it’s set at any point, the game starts to update the colour RAM as quickly as it can, so it’s ready by the time it has to present the next frame. It also keeps track of the diff between the current and the upcoming frame to minimise the time needed for the update, i.e. it won’t write colour bytes that don’t change.

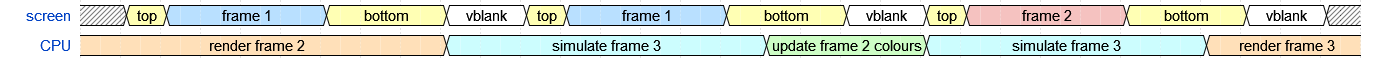

Here’s the timing diagram for a typical frame transition (top and bottom correspond to the static parts of the screen above and below the 3D viewport):

In general, simulation takes a bit longer than a full round-trip for the raster beam, so we can definitely complete work on the upcoming frame before we have to start clearing the screen we’re currently showing.

Unfortunately, this approach didn’t seem to work well when adapted to the Plus/4. The problem is that colour information is doubled due to the extended palette, i.e. we need to write two bytes instead of one for each character block to update both the chroma and the luma components. As a result, the update step takes longer, and if the polling for the marker flag happens too late, it can miss the deadline before the new buffer is to be shown. In short, the sky-ground separator line kept flickering regularly.

To solve this problem, I changed the logic so instead of setting a flag in the interrupt, I perform the colour update right away. This is a bit annoying, because it requires backing up several zero page variables used by the routine, but in the end it’s a lot more robust than waiting for the simulation logic to get ready to check the flag. In the end, all visual glitches are gone.

I could have sidestepped the issue if I had chosen to set the same luma level for the sky as for the ground (because one byte holds the two lumas, while the other defines the two chromas of the individual block colours), but that would look too muddy and lacking contrast. Also, while technically double buffering would be possible, there’s simply not enough memory for an additional colour buffer.

Reimplementing Sprites

The last big piece of the puzzle was to reimplement all functions in software that were done with sprites in the original. These are the following:

- messages at the top of the viewport

- dashboard display

- boost flames

- wheels

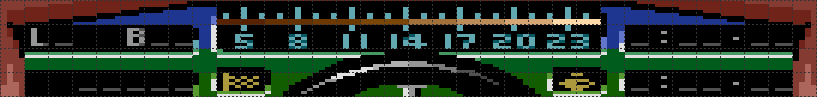

Let’s look at the picture again with the sprites marked up:

The dashboard was the easiest: I redesigned the original so that all digits are aligned with the character grid, so they can be drawn without the need to shift bits or to perform any logical operation with the contents of the screen.

As for the messages (like the PAUSED text above), I opted to just draw all possible messages as bitmaps instead of implementing a text rendering system. I devised a simple compression scheme where every character block takes three bytes (just packing the bits tightly), and if I need to show a message, I uncompress it into a buffer that can be ANDed with the contents of the screen as a final step. The 15 possible messages take up less than 400 bytes altogether this way, while the C64 original also needs over 200 bytes to store them in string form, so the extra memory requirement is not too bad.

The flames coming out of those exhaust pipes first looked very daunting, especially since they occlude other visual elements that are already fully coloured. After some thinking, I realised that by making them a tiny bit smaller, and adjusting the picture of the closest pipes just by a single pixel so I could stay within the character boundaries and keep away from parts of the viewport where lines are being plotted, there’s no need for masking at all. The flames could be simply drawn into the car front image to generate alternate versions to show depeding on boost status:

There are only two animation frames for every flame, and I get to flip between them for free by assigning them to each screen buffer statically. The front of the car is added to the screen buffer in the beginning, during the screen clearing step, so all I need to do is pick the correct variant, which makes this effect essentially free. Also, I’m not storing the full alternative images, just the parts that differ from the default empty pipes. It’s also fortunate that the colour buffer doesn’t need to change between the three images.

Finally, I had to deal with the wheels, which is the most complex sprite-based element. On the one hand, the Y position of wheels is driven by the load on the suspension, i.e. they interact with the physics simulation. On the other, we cannot rely on the main update cycle to animate the treads, because that would be too slow to give any sense of motion, so the spinning animation is tied to the screen refresh cycle. The C64 original updates the wheel animation frames in the raster interrupt routine, and I had to do the same. While doing this on the C64 takes just writing two bytes to specify the sprites shown on the two sides, on the Plus/4 we have to draw the changes straight into the bitmap.

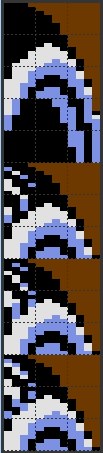

In order to make a smooth and efficient update possible, I had to think a bit about how to build up the wheel images so they are correctly masked by the pipes (achieved for free on the C64 via sprite priorities). Let’s look at the final version in the editor for reference:

When plotting the wheels, we deal with four different parts, each of which receives its own special treatment: the three character columns of the base image and the tread surface, which is limited to overwrite a certain part of the first column. The base image is blitted into the current back buffer right after adding the car front image, before starting to plot the lines. The three columns are drawn the following way:

-

The outer column is just written into the screen buffer from the current Y position until we hit the little pipes. I’m adding a single cyan pixel from the pipes to cover each wheel, just to cover up character boundary. If you have eagle eyes you might have noticed that these pipes are not present in the C64 version. The reason I added them was to prevent the wheels from affecting the part of the screen that’s not double buffered. If you look at the Amstrad CPC version, you can notice something similar going on, and I wouldn’t be surprised if it’s for the same reason.

-

The inner column is also just written into the screen buffer, but it gets cut off earlier by the top of the closest pipe. Since that happens to be a straight horizontal line on a character boundary, there’s no need for masking.

-

The middle column that contains the top of the inner rim is the only one that needs to be masked, because it’s occluded by the pipe. So unlike the others, this part is ANDed with a pipe-shaped mask first, then ORed together with the currently active image of the pipe (the side of the closest flames shares the same bytes).

At this point we have wheels without surface animation that respond to the physics simulation just like the original. I adapted the treads so they only cover a smaller part of the wheels, exactly the part that’s always fully visible. This allowed me to use the simplest plotting logic possible, not even having to cut off the bottom of the animation or mask parts of it. Note e.g. that the topmost pixel row of the wheels doesn’t take part in the animation, because that row doesn’t cover the full byte. To make the animated part narrow enough (just four multicolour pixels), I faded it out from white via the colour of the sky, so it kind of looks like it’s reflecting the sunlight.

Finally, the grey parts of the wheels had to be tinted with the colour of the sky to avoid colour clash. It’s surprisingly subtle, and almost gives it a feel of global illumination, which I consider one of the happy accidents of this transformation.

Outside Gameplay

Having finished work on the gameplay, I had to tackle the problem of fixing the looks of the menu. The fact that the TED’s video modes match the VIC’s one-to-one was extremely helpful here, since I didn’t need to touch any of the drawing and text rendering logic. The only aspect that was broken was the colour, so I had to completely rewrite all code dealing with the screen matrix, and also adjust all the colour data by hand. This was mostly drudgery without any particular interesting new insights.

All the image assets and colour information are RLE compressed on the fly using Kick Assembler macros, and they ended up smaller than in the C64 original despite requiring twice as much colour information. This is because colour buffers were originally uncompressed, as they could be stowed away in places that wouldn’t be otherwise useful on the C64 (e.g. under the I/O area), but the Plus/4 really needed the extra space.

Finally, I was pleasantly surprised to learn that the KERNAL API for file operations is fully compatible between the two systems. In fact, it’s even binary compatible, as the same syscalls have the same addresses. This was a huge relief, because it meant that I didn’t have to reimplement all the careful error handling logic from the original, just lift it unchanged. I did however remove the encryption logic of the original, because it felt like a waste of valuable space, so the Plus/4 save files are not compatible with the ones created on the C64.

Conclusion

This project was my first foray into the world of the Plus/4, and my general take-away is that it’s a fairly pleasant system to program for. They clearly made an effort to streamline some aspects of the predecessor, and the I/O interface feels better organised as a result. ROM/RAM banking is also much more convenient to use. Ignoring the lack of sprites and the very limited sound capabilities, there are still those typical Commodore trademark anomalies like register $ff12 (bitmap base address and the high bits of one of the sound frequencies packed in a single byte), where a lot of pain was inflicted on future programmers of the system just to save a bit of money somewhere in manufacturing.

The extended colour palette really does a lot to elevate the game, both during gameplay and in the menu. Maybe this is good place to thank Unreal, a long-term member of the Plus/4 scene, for reinterpreting the original title screen in glowing TED colours. It really does set the mood right from the start for what I believe is the best-looking 8-bit port of this game.

Happy racing!